Introducing Ela Orleans

An interview between Ensemble Klang’s artistic director Pete Harden and new Associate Maker Ela Orleans about her new projects with Ensemble Klang for 2025 and beyond.

1. Beginnings

Pete Harden: Where do we start?

Ela Orleans: I think we can start with how we met? We met through a mutual friend who had been trying to help me push my career in new directions and challenge me. I was known for my pop productions, but my interest in music was always much broader. In Poland, the attitude toward music is very conservative — you’re expected to go from primary school music to secondary and continue your music education step by step up to the conservatoire, or you’re not considered a “real” musician.

My path was different. I went to primary school music, and I played violin as a child, and later some piano, but after suffering a concussion I had to give it up because I developed serious migraines and problems playing in the orchestra. So I turned to visual arts and theatre, and eventually, after a long circle, I came back to music and did a PhD. While I was studying for that, I was picked up by Cryptic, an audiovisual lab in Glasgow, through my university tutor. That opened a new path for me — more ambitious, interdisciplinary work.

I’ve always oscillated between visual art and sound. For me, music often starts with a visual or literary idea. I think in terms of spectacle — though for a long time, I didn’t know how to realise that or didn’t have the means. Cryptic gave me that sense that I could actually do it. That’s where our paths crossed, via Cathie Boyd from Cryptic. And I remember thinking, “Ensemble Klang are far too cool for school; they’ll never be interested in working with me!”

Pete Harden: I don’t know that we ever feel that cool! But listen, you covered a lot just now — quite a journey from a concussed child to completing a PhD in Glasgow. Tell me more about that journey. You mentioned turning to visual arts — what was your relationship with music through those years?

2. Inspirations

Ela Orleans: Cinema was probably my strongest audiovisual experience growing up. My father would take me to church on Sundays, but the real reward was that afterward, he’d drop me off at the cinema for the children’s matinee. I’d sit there for hours, completely mesmerised. That world never seemed to end for me.

Later I understood that it was about total immersion: the experience of another world. As a child, I never really fitted in; I didn’t like school, so cinema became my parallel existence.

Pete Harden: And through cinema, people have been exposed — perhaps without realising it — to some radical and experimental music. Throughout the 1980s, ’90s, even into the 2000s, there were extraordinary film soundtracks, sometimes that were more experimental than what was happening in concert halls.

Ela Orleans: Yes, absolutely. And one composer who meant a lot to me was Penderecki. He was not embarrassed about writing for film. He managed to use his artistry in film scoring in a way that felt truly innovative. The score for Saragossa Manuscript is a masterpiece. And of course there are Herrmann and Morricone the list never ends.

Pete Harden: Are there any particular soundtracks or films from your youth that have stayed with you?

Ela Orleans: Definitely. Jean-Pierre Melville’s films, especially Le Cercle Rouge, made a deep impression. The composer, Éric Demarsan, is a favourite. Sometimes I couldn’t tell whether I was imagining it or the music was really there; that’s how seamlessly it worked with the image.

And then Miles Davis’s Ascenseur pour l’Échafaud. I was fascinated when I learned how it was made: entirely improvised. It required such focus and dexterity. Technology allows me to work at my own very slow pace, but that level of immediacy is something I admire deeply.

Fassbinder’s Berlin Alexanderplatz also had an unforgettable soundtrack by Peer Raben; again, the combination of image, sound, and human voice was something I found profoundly moving.

I’ve always loved when sound and image coexist — when you hear the grain, the texture, the imperfections. I hate when people talk over music, but I love when there’s a kind of living noise in the background — it makes the sound alive, situated in space.

Pete Harden: Yes, that’s maybe the subject of your work — the combination of the visual and sonic, paired with the live experience?

Ela Orleans: Exactly. And storytelling. I think I’ve never been able to choose one “favourite” thing. The moment I decide something’s my favourite, I think of another thing I love just as much. I don’t like making lists — art is about openness for me.

3. Creations

Pete Harden: When did you start upon this creative path of yours — composing, performing, creating this unique body of work?

Ela Orleans: It began almost by accident; my friend saw me walking with a violin I just bought. He called me up and said, “Come play with us.” I was terrified of the instrument, but I agreed to play a few notes.

That project became Radio Tuesday in Glasgow — an experimental music night. From there we formed a band called Hassle Hound. We toured a lot in Germany and England, and released several records on the Pickled Egg label. Even John Peel played our music on his show — we were meant to record a live session with him, but sadly he passed away before it happened.

After that, I decided to go solo. I realised that in group settings, especially as a woman, having strong musical ideas could be interpreted as egotism. It was a fine line to walk, and at the time the industry could be very patronising. When I moved to New York and started performing solo, it was incredibly stressful. I developed stage fright and nearly gave up performing altogether. Then I started to post small things on MySpace and that’s how I got my first records published by small indie labels.

Pete Harden: And your background in theatre seems to influence your performances too.

Ela Orleans: Very much so. I always wanted my shows to feel like a spectacle — something people remember visually as well as musically. I iron my shirt or costume, do my nails, fast before performing — all those rituals help me prepare. I want the audience to experience more than just “me standing there.”

Over time, I became bored with certain performance formats — artists hiding behind screens or doing the same setups. I wanted to bring theatricality back, to combine my love for archives, visuals, and sound. That’s how my PhD also began — through questioning authority and originality, and through exploring what it means to reuse existing material.

Pete Harden: Let’s touch on your PhD briefly. Geographically, your story travels from Poland to Glasgow and now Paris, all via New York. How did that unfold?

Ela Orleans: I went to music school in Poland first, then art school, then theatre school. Through that, I met people from the theatre scene in Glasgow while working as a waitress on the side. Eventually, I went back to Warsaw, then on to America after meeting the Wooster Group and I stayed in New York for seven years. When I needed a change I went back to the UK because many of my friends were there, and I stayed in Glasgow for a while. Then, after Brexit and the pandemic, I decided to move again. I wanted to live somewhere with both beauty and good healthcare, and to be close to places like Holland or Austria without having to fly all the time. My mother also needed support, so I wanted to be in the EU; just in case.

Pete Harden: When you were in New York, you were already creating your own work using archival footage and existing material. Was that when you began to encounter questions about legality and authorship?

Ela Orleans: Yes, definitely. I was careful, but some of my friends got into trouble with sampling — for instance, using songs by Françoise Hardy without clearance. I tried to be clever about it: manipulating the samples, obscuring their origins, or using materials from composers who didn’t mind, like Morricone.

But over time, I started questioning that whole DIY world. Sampling seemed less creative and more a like copying. So when people today get squeamish about AI, I find it funny; artists have been doing a kind of “manual AI” for centuries. The difference is that machines do it more efficiently.

4. Studies

Pete Harden: Your PhD explored those issues.

Ela Orleans: Yes — it was about moral rights, the right to use archives, and the concept of originality. I was interested in how the industry punishes the wrong people: small, creative artists who repurpose material are targeted, while giant corporations get away with exploitation. Spotify, for instance.

So my research looked at the ethics and the absurdity of ownership in art.

Pete Harden: Did the PhD change your creative practice?

Ela Orleans: Completely. I stopped relying on found material and began making my own “samples” — recording everything myself. For example, in Night Voyager there’s only one borrowed sound: the archival NASA recordings of astronauts Aldrin and Collins. NASA gives full permission if you credit them, which I think is wonderful. That attitude toward openness and sharing feels healthy — almost utopian.

Pete Harden: That’s a sort of old-fashioned, frontier idea — shared discovery and exploration.

Ela Orleans: Exactly. And I think originality is a myth. Nothing has been truly original for a very long time. The more we learn about the history of music, the more we see how much everyone has borrowed from everyone else.

Take Bob Dylan, for example — he’s copied almost everything, even parts of his Nobel speech. But he does it in such an ingenious way that it becomes art again. He’s a genius of transformation rather than invention.

That’s what fascinates me — not pure originality, but the creative act of recombination. The same is true in painting: so many “genius” artists had assistants or borrowed motifs. What matters is whether you can create a new world for the viewer or listener — a space that feels alive and transformative. If someone leaves my performance feeling even a little changed or uplifted, that’s success.

Pete Harden: That’s beautifully put! I’d like to talk about your collaboration with Ensemble Klang. You’re now one of our Associate Makers, which we’re thrilled about.

Ela Orleans: I still can’t quite believe it!

5. Night Voyager

Pete Harden: You fit perfectly into the kind of artist we love working with — interdisciplinary, self-defining, and fearless. We have two big projects ahead: a new version of Night Voyager and a brand-new large-scale work, Forma Nubium, about clouds. Tell us a bit about Night Voyager first.

Ela Orleans: Night Voyager grew from my fascination with NASA — not just the imagery but the generosity of how they share their archives. Their 16mm and 35mm film collections are astounding. My friend Stuart McLean was friends with Steven Slater, who was the archival producer for the Apollo 11 documentary.

One night Stuart called me and said, “Steven is happy to work with you!” I couldn’t believe it. Suddenly I had access to tens of thousands of hours of NASA footage. The question was: how to make something new out of such familiar material?

I realised that what interested me most wasn’t space itself, but the human side of it; the bravery, the fear, the loneliness. So I started looking for literature that dealt with those themes. That’s when I found Night Thoughts, an 18th-century poem by Edward Young. It’s deeply Christian, full of pathos, and at times unintentionally funny, but also moving in its meditations on mortality and faith.

While working on it, I cut up and reassembled Young’s text, using William Burroughs–style collage techniques. I juxtaposed fragments, added my own lyrics, and connected it all with the NASA imagery — astronauts floating in silence, wives waiting at home, a mixture of cosmic and intimate.

Pete Harden: That sense of the human condition — risk, love, mortality — runs through the piece.

Ela Orleans: Exactly. I was drawn to how people risk their lives for wonder, for discovery, for something beyond themselves. It’s both heroic and absurd. Night Voyager became a meditation on that and the fragility and beauty of human striving.

Pete Harden: There’s a beautiful balance in Night Voyager between the archival and the personal — between NASA’s vast imagery and your own inner landscape.

Ela Orleans: That balance was very important to me. The film footage is extraordinary, but I wanted to bring human aspect into it and to explore what it means to look into the unknown and to feel both wonder and fear.

In the piece, I use not just the images but also the astronauts’ voices, sometimes fragmented or distorted, to make them feel like ghosts or memories. There’s something spiritual in that. The music and the visuals unfold slowly, like meditation. I wanted it to be both immersive and contemplative and less not only about the space but emotion.

Pete Harden: And we’re excited to add some Ensemble Klang instruments and performers to your fantastic solo version, to create this multicoloured new live version!

Ela Orleans: I’ve always felt that music should live in space, that it should breathe, so that you can sense the air around the sound. Ensemble Klang’s contribution is absolute dream team to achieve that.

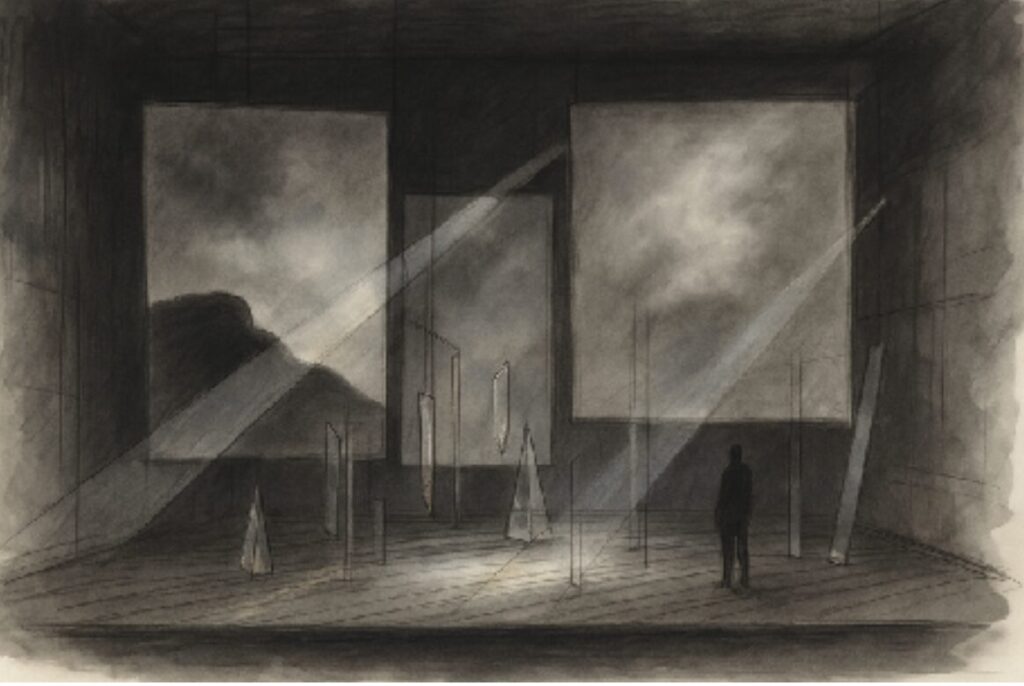

6. Forma Nubium – The Cloud Piece

Pete Harden: In parallel to Night Voyager, we’re working together on your next large-scale project, Forma Nubium. Can you tell us about that?

Ela Orleans: Forma Nubium began during a flight back to Paris after my father’s funeral in Poland. As the plane descended through clouds, the city lights appeared and vanished in mist. There was something consoling in that moment, the sense that movement itself could be steady, that change could hold a kind of peace. From that experience grew a work about perception and transformation. The title plays with that idea — “forma” meaning shape, “nubium” meaning of clouds.

The work will combine sound, film, and text again, but this time I’ll join forces with Ensemble Klang’s regular collaborator, the light designer Pavla Beranova.

Pete Harden: It also feels like a continuation of your theme of space — not outer space this time, but atmospheric space, the space between things.

Ela Orleans: With Night Voyager, I was looking up into space. With Forma Nubium, I’m still looking up, but closer to Earth, into something that’s around us every day and yet mysterious.

It’s about perception, really how something so common can be endlessly fascinating when you pay attention to it. And again, it’s about the human condition: impermanence, change, beauty, loss.

Pete Harden: That’s a poetic concept!

Ela Orleans: I’m interested in the spaces between sound and image, between consciousness and dream, between the personal and the universal. Clouds are the perfect symbol for that, they’re always in motion, never fully there. Forma Nubium follows this long human fascination with clouds, from their ancient and medieval symbolism of the divine to the early scientific urge to understand how they refract and scatter light. At its centre lies Roger Bacon’s optical writings and diagrams from the Opus Majus, where the cloud becomes not only a veil but a lens.

Fragments of Latin text from Bacon’s Opus Majus are whispered and sung: phrases describing light multiplying within a transparent medium, or the rainbow formed in the cloud. They surface and dissolve like traces of thought carried on air. Forma Nubium is not an attempt to recreate the fluffy image we all know too well but a meditation on impermanence, perception, and light. It explores how clarity and obscurity coexist, how order can emerge within change, and how, even in moments of loss, the shifting sky can feel like a kind of home. Ensemble Klang is at its very heart and I am very happy to have such wonderful artists to build it with.