Keir Neuringer’s Elegies & Litanies

This is an edited transcription of a conversation between Thomas Stanley and Keir Neuringer that took place on 18 October 2020, leading up to the release of Keir Neuringer and Ensemble Klang’s album Elegies & Litanies.

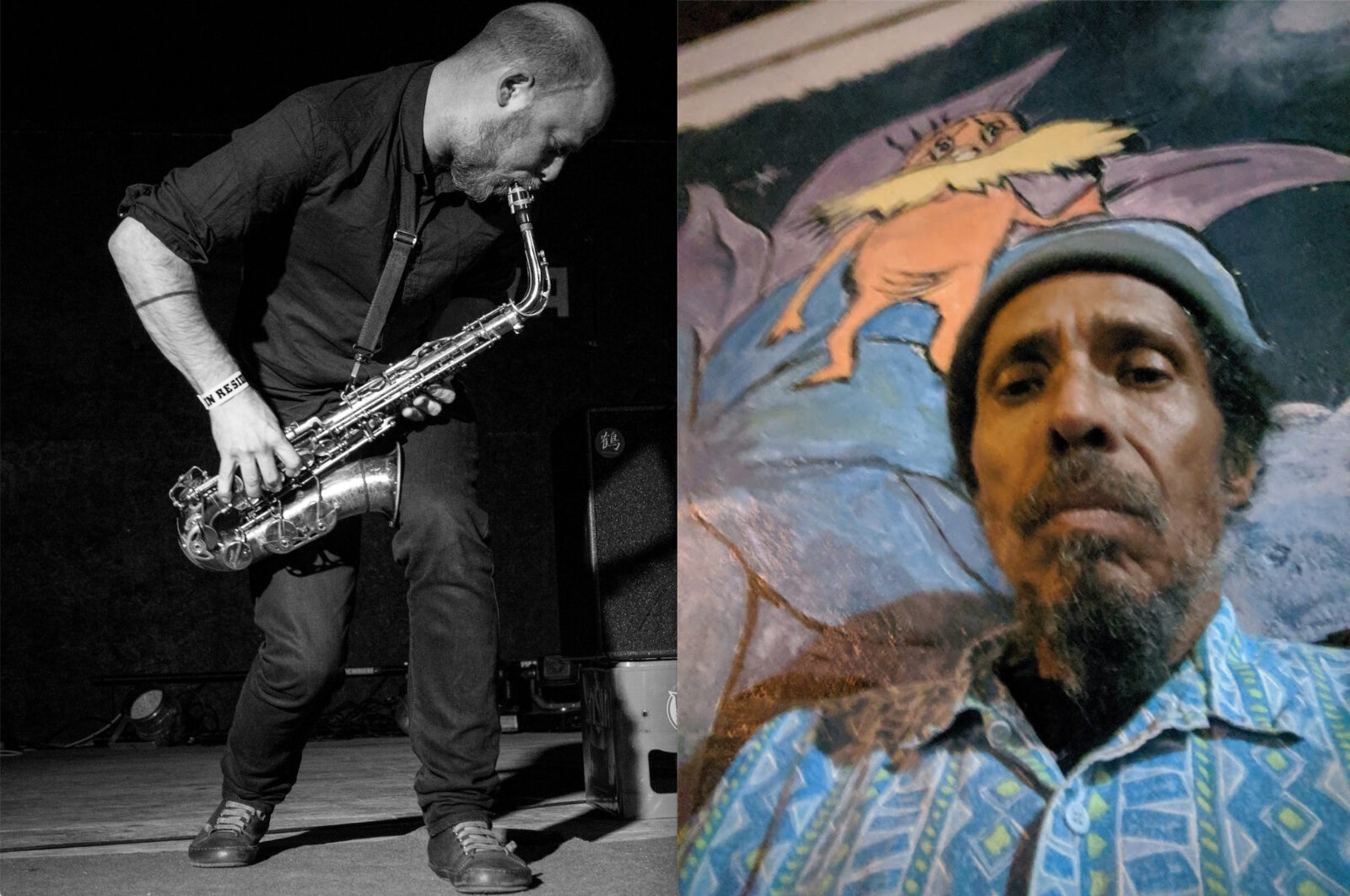

Thomas Stanley (a/k/a Bushmeat Sound) is an artist, writer, and activist committed to audio culture in the service of personal growth, noetic (r)evolution, and Justice. As performer and curator, his audio work employs musical sound to anchor, frame, and accelerate our subjective experience of history. In 2014 he authored The Execution of Sun Ra exploring the ramifications of Alter Destiny, Sun Ra’s unique construct for a just and sustainable Future.

Gloom, Hope & Fixing the Problem

Keir Neuringer (KN): How’s it going?

Thomas Stanley (TS): It’s going well. Nice recording.

KN: Thank you.

TS: It’s got a touch of gloom to it, I’m not gonna lie. [Laughs]

KN: Well, yeah, my work sometimes does that. It is what it is, and when it is, you know?

TS: Yeah I got that. It would seem out of place if it didn’t.

KN: I mean perhaps there’s an argument to be made that in times like these expressions of joy are a necessary thing also.

TS: They’re as acceptable as interstitial palliatives but they won’t fix the problem. They’re necessary food, those expressions of joy, but they’re not the diagnosis and they’re not the prescription, that’s for sure.

KN: True, true. I don’t know that gloom fixes a problem either. It observes a problem. Or maybe it processes a problem.

“the optimism of the work is in the doing of it, with other people, for other people, for you to hear. That way I feel myself part of something. I’m not asking of myself to figure it all out. But to be part of something.”

TS: In your liner notes you describe the Elegies as ways of dealing with memory of loss that is tragic and total. And even as a way of monumentalizing the experience of that loss. The work does not repair the loss, the work doesn’t pretend to cap it off with anything like a rosy optimistic ‘but it all works out in the end’ kind of summation. And I’m trying to figure out how do you bring an audience — and I’m not suggesting you haven’t done this — but how do you bring an audience into this realisation of loss that you can’t resolve for them. How do you bring us into that? How do you start this journey?

KN: I appreciate that question. I think that if I want to give an honest expression of my feelings through the work, and I don’t have a rosy punctuation mark to offer, then finding a way to do that would be moving my art into marketing of some sort. On the album, Elegies is Side A, and Side B starts with Thoreau Day (for Kadri Gopalnath) and ends with Litanies of Trees. Once Ensemble Klang and I realized we were going to produce an album, I composed Litanies to kind of balance things. It doesn’t answer Elegies and it doesn’t present, like you’re saying, some kind of rosy optimism or something. It just balances it in tone. If anything, any optimism I feel sits in the work that I did together with Ensemble Klang—or the cooperation that I enter into with the listener. I create a work, and you listen to it, and that’s the optimism. Not in the content of the work.

“When I'm circular breathing, silence is implied, but it's not literal. And I think that affected my composing for sure.”

Saxophone, Breathing & Kadri Gopalnath

TS: The first time I heard you play, Keir, I was really struck by your breathing, by your use of breath, by your use of circular breathing—how much you could get done, or seemed intent to get done, with a single breath or a single cycle of breathing. I was not aware of the work of Dr. Gopalnath. And I went and looked up and was so pleasantly surprised to come into an awareness of this person who had invested so much into making the alto saxophone a fit vehicle for Carnatic expressions. Anybody that’s been into any kind of yogic practice or meditation that comes out of India is aware of the metaphysics of breath. And that’s what caught my attention when I first heard you. And your album Ceremonies Out of the Air brought that even more into focus. So it was cool to learn a little more about Kadri Gopalnath. I’m sorry about his loss.

KN: Yeah, he died about a year ago. I got to see him a couple of times. I once saw him with Evan Parker. I saw him on his own a few times. The last time I saw him was on Le Guess Who? festival in 2018. I was there with Irreversible Entanglements.

TS: Had you already come to where you are with your own personal style as a sax player when you got into his music? Was he somebody who was an influence at an early stage or later? Or not at all?

KN: Well, I’m still learning! I’m still trying to figure it out. I saw him for the first time in Manchester, England when I was 21, around the same time I was getting into Evan Parker. As a teenager I was into Maceo Parker, Charlie Parker, Sonny Rollins, Pharaoh Sanders…

TS: Did you know Arthur Blythe?

KN: Not at that age. It was much later that I heard him and started getting into people like Roscoe Mitchell, Ornette Coleman. I even came late to Coltrane. But around 20 or 21 I started hearing players like Henry Threadgill, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Evan Parker, and then Kadri Gopalnath, Albert Ayler. That’s where it’s like ‘oh shit!’ And because it changed the way I approached the saxophone it changed the way I approached composing, eventually. I was thinking today about how there’s not a lot of silence on this album. With my saxophone playing, when I’m in a circular breathing situation for half an hour, silence is implied but it’s not literal. And I think that affected my composing for sure.

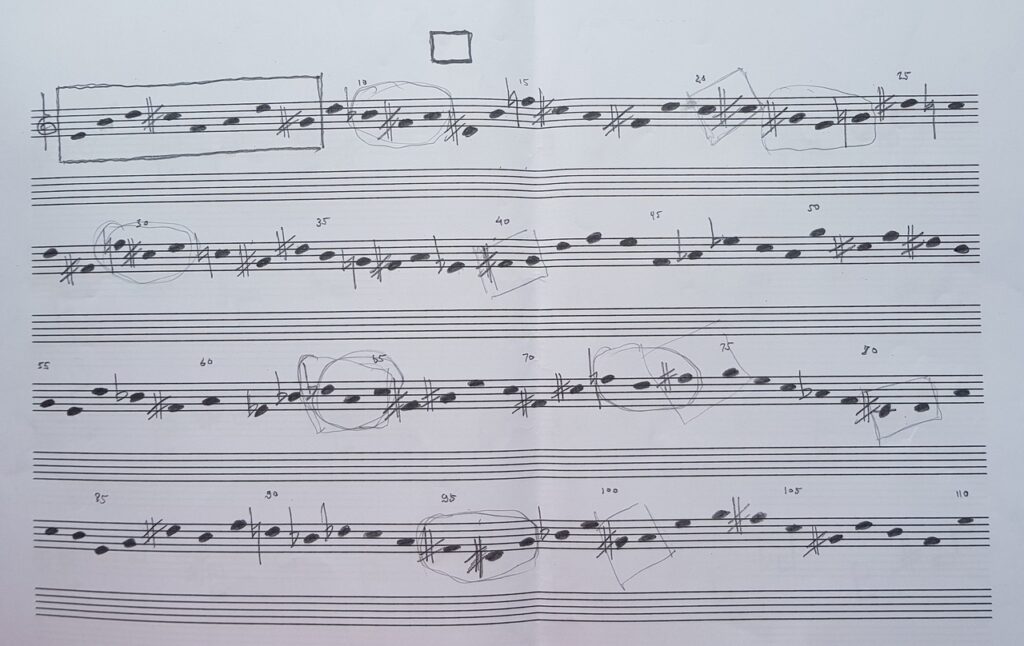

Score for Elegies at the Border I, Keir Neuringer

Score for Elegies at the Border I, Keir Neuringer

Score for Elegies at the Border II, Keir Neuringer

Score for Elegies at the Border II, Keir Neuringer

Composition, Collaboration & Scores

TS: I’ve got your score in front of me. And I love your square, and triangle and circle [the indications for the three parts of Elegies]. I also notice that you really write with density, that the space is full, and there’s always interaction between voices. And the canon and the counterpoint just create this sense of environment, that was consistent throughout. You were being moved by these different environments that were made out of sound. I like that kind of feeling, that kind of fullness.

KN: It’s not on the page as much as it’s in the interpretation of the page. I’ve known and worked with the Ensemble Klang people for nearly 20 years, since before they formed the group. So there’s something about the way I wrote these pieces, I guess economically. What you talk about, the counterpoint, you wouldn’t necessarily see it in the score, but you hear it. Another joyful thing in this gloomy piece, in these gloomy pieces, is the pleasure of being able to show up at the rehearsal for the recording, and say ‘look, here’s a page of music, we’re going to make 15 minutes or half an hour of music out of this.’ And they’re just like, ‘yep, let’s go!’ So we start, and I can say ‘let’s try this another way’, and they can ask ‘can we do this?’ You know I was trained in the more rigorous European classical tradition…

TS: Where a score positions every sonic event.

KN: Yeah. And I just haven’t written music like that in a long time. And this is the first recording of my notated stuff. And I didn’t have to go there. There’s a lot of trust. I don’t want to denigrate the entire history of Western Classical Music, whatever it’s called. I get a lot out of listening to Bach, or Beethoven, or Bartók. I get a lot from those people and their work. But it’s nice to be able to ask of myself, to imagine a different world, and to just push a little bit, a little bit. And this isn’t radical, I don’t think of this music as radical in any way, but a little bit. It pushes a little bit against that tradition.

Score for Elegies at the Border III, Keir Neuringer

Score for Elegies at the Border III, Keir Neuringer

Borders, Culture & the Imperial Mind

TS: Keir, the border. I was traveling through Europe on the way to a conference in North Africa and I was traveling with a group of people that included a man named Twiggs Xiphu, this was in the mid-80s. And Twiggs was a South African activist who had been in prison and tortured with Steve Biko. Part of the Black Consciousness Movement. So we’re arriving at the airport [in Paris] and we’re lining up. The line is heavy, a lot of people, we’re getting closer to where you’re actually going to go through the checkpoint and they’re separating us according to whether or not you have a U.S. passport. So me and the other folks on the delegation who had U.S. passports are in one line, and my friend Twiggs is in the much longer, much more raggedy, less well-treated line. And I was shocked to find myself standing before signs that my parents had seen marked ‘white’ and ‘colored’ only on that day I was in the white line. Talk about borders, Keir.

KN: Yeah. Shit. There’s a spot in the first text where I say something like ‘you are not on the list’ — I’m implying that you don’t wanna be on the wrong side of the list and then I kind of switch the perspective and I say to the listener — the implication is that we’re all on the wrong side of this shit together. And then for a couple of lines I switch the implication and say ‘you are on the list’. You’re good (or you’re not good, depending on your perspective). Because if you’re not on the list, where are you? What does it mean that you’re not on the wrong side of this shit, you know, the receiving end of this shit. And I think about that a lot. It touches on the ideas of ‘allyship’ or ‘accomplicing’ right? That a lot of people have talked about these days, whether one considers oneself an ally or an accomplice and how that changes what one does. You know, because we can’t really change what we’ve come from, what our past has been.

“you have to be a monster not to weep for the way we’re losing whole species, whole entire groups of people, languages”

TS: The title is Elegies at the Border and you talk about that border being referential to ‘a specific border, all borders, and the borderline between what in our culture is salvageable, redeemable, and all that is not.’ Do you weep for what is not salvageable from culture? That evaporates before our eyes? That is irretrievably lost?

KN: There are some things that I definitely weep for but there’s a lot that I don’t weep for and in fact there’s a lot more that has to go.

TS: The world is technically outside of culture. So are the losses that you’re most lamenting in this elegy — because you really go through a list — it is, boy, man — you know, sawdust, I love that. But are you lamenting the loss of something that is within culture or are you lamenting the losses that are happening in the world?

KN: There’s a little of both, I have to say, with the losses in the world, you have to be a monster not to weep for the way we’re losing whole species, we’re losing Arctic summer ice, we’re losing whole entire groups of people, languages, which is inside of culture, it’s in the world but it’s culture, we’re losing languages. I don’t know if I want to say ‘we’. We’re losing it, but somebody is taking it, someone is destroying it, someone is robbing people, and has been for as long as there’s been history, robbing people of their land-base, and their customs. When cultures go, and their languages go, knowledge goes, ways of surviving in the world that don’t depend on our extractive culture, our cruel culture. There have been and continue to be cultures that aren’t this cruel, that aren’t based on cruelty and destruction. We lose that knowledge, we lose access to that knowledge when we destroy the languages, when we break up those cultures.

TS: You talk about this culture of cruelty, and I want to peel that back some, and see if you believe that there’s some configuration of consciousness that is at the basis of this extractive, imperialist-capable culture. What is the Imperial Mind? And where are we at with it? If it has an expiration date, or an antidote?

KN: Well, this is not the only antidote, but one of the antidotes is what we do, what you and I do. What our comrades do. We’re doing it. What would things be like if we weren’t? Another antidote is not something that one speaks about over the telephone. But I do feel comfortable saying that people who are absolutely and utterly committed to cruelty on a grand scale only understand violence. I saw it in The Black Power Mixtape, the Stokely Carmichael statement, I think he was in Sweden giving a speech and talking about Martin Luther King, and saying King’s error was thinking that you could use shame against your oppressor, where for example, with the US, there’s no shame. So, on the one hand, speaking of antidotes, what you and I, and what our comrades do is one. On the level of Culture. Another is responding to cruelty with violence, which I think can be legitimate and can be necessary.

TS: At some point the scale at which you, at which we, draw the problem, the response has to be as large. And I know, because I’m a little bit older than you, a little bit. I have a consciousness that gets back a little closer to things that were still possible in the 60s and 70s even. And I’m disturbed that language has changed such that we really don’t have much left beyond protest culture in which to push back, and protest culture, once you’ve permitted it and you’ve got police escorts, it’s sanitised. I really stopped going to protests, I forget which Iraq war it was, was it the first one or the second one? And I realised this is all really orchestrated by the people that I think I’m in opposition to while I’m out here. And yet I’ve got to go back and tell you that I’m not sure if the authors of violence can be taken down with their own weapon, I’m not sure if the people can ever pull together enough counter-force that is in a strict sense violent counter-force, to turn off the police-machine, to turn off the soldier-machine, to turn off the state. I just think that they feed on it, it’s an energy they take in, and it creates all sorts of permissions, and they’ve already built up this arsenal and they’ve been looking for a reason to use it, to see if it works.

KN: Well no, I hear that. Even the thought, and the way I expressed it, I don’t think it’s very useful. I don’t embrace it with any kind of joy. I recognise that some people get to the point, where despite being out-gunned, completely out-manoeuvred and out-gunned, they’re not willing to sign their own death sentence. I think of Korryn Gaines. She was a young Black mother, I can’t remember if it was Baltimore or DC. A couple of summers ago, who was approached in the same way so many victims of police brutality are, with lots of police guns drawn. She had her child in her house. And she fired back. And they fired at her, it didn’t matter that she had a child in the house. There was an hours-long stand off, and they killed her.

TS: This happened right outside of Baltimore, and it was a Baltimore SWAT team.

KN: Yeah, she was out-gunned. I don’t think there’s anybody who could say, ‘well this is what she should have done.’ What should have happened is, instead of killing her, the cops should have gone home and quit their jobs, that’s what should have happened, that’s the only thing that should have happened in my opinion. I get heated even thinking about it. There’s no one that can say to me what she should have done differently, because it wasn’t on her. It wasn’t on her. Whatever their excuse was, it wasn’t a life-threatening situation where it was better to shoot into the house with a child, than to work it out some other way.

Jazz Music & Avant-garde Dissent

TS: Except that you can kind of see in each of these incidents which are all a part of the same constellation of cruelty that this woman’s whole thing starts because a warrant was issued because she was driving without a license plate, and she picked up a bench warrant and the cops were coming to serve the bench warrant, but that really isn’t the issue, the real issue is the authority of the police to act on behalf of the state, and that authority can never be optional, that authority has to be in all instances and in all cases, notwithstanding small children in the apartment, or the three boys who watched their father, Jacob Blake in Wisconsin, Kenosha, take seven bullets in the back. That’s the offence. That kind of harsh demarcation of authority, that’s the way that slave authority worked, that’s the way the plantation system understood the role of the overseer. It’s not enforcing particular infractions, that’s not really going on, what’s going on at a deeper level, is this enforcement of the authority of the state structure. The Imperial Mind, the mind that produces police, and imperialism, and atomic weapons, and a context within which you can rationalise their use. Some, in its defence would argue that the Imperial Mind gives us order against wildness. And at the end of the day, you and Thoreau and everybody else need to be more realistic and accept that without the Imperial Mind you’d be lacking a lot of things… including Jazz music, which might even be seen as a way of institutionalising the wildness in humanity and making it into a product that is suitable for distribution through capitalism. Talk about that. That you don’t have a better game, than the game that has been concocted by everything that has happened since Columbus.

“The avant-garde is permitted to provide us an escape valve for dissent.”

KN: I’m going to pick right up on what you said about Jazz music. I don’t think of Jazz music as a fixed thing. I think of it as many things. What Jazz music does for me, and the way I participate in it, isn’t permissible through imperialism and capitalism. It’s not specifically… while it is on one level a music that evolved out of New Orleans, out of military instruments being left in New Orleans in the south after the Civil War, and African people picking up those instruments and creating a new music with them, it’s partially that. But that’s because of those specifics, but the aspiration in the music, what the music insists on. That’s not a gift of imperialism.

TS: The avant-garde is permitted to provide us an escape valve for dissent.

KN: You believe that though?

TS: No [laughing], I’m just saying… one could speculate that that’s what’s going on!

KN: I had a professor who was very insistent, and I don’t know what the current scholarship on this is, that Cage worked for the state department or something, or the CIA. I don’t doubt it. I don’t need it. I do care, but on the other hand, I’m going to do my thing, I’m going to engage the collaborators, the observers of my work, in a genuine way. And there may be something outside of us that permits or prevents certain parts of it, but I’m not thinking of it when I make my work.

TS: I want to take you back to the work that we’re talking about, which is a great recording that you’ve done. And I don’t want to give you the impression that I didn’t appreciate listening to it, a lot. It’s a very deep listening, it’s very rewarding music to take in. So the way Elegies is set up. The first part has a text and the third part has a text, the second part does not. Elegies I could be seen as a diagnosis. And if Elegies I is a diagnosis then the third part really reads like a prescription, and it’s a prescription in the form of an incantation, a spell, I mean you’re calling on forces and numerology and the essence of numbers and the essence of language, and I wonder if you’re edging us in the direction of… Is there something magical about how history is unfolding, about how history works?

KN: I don’t know. But I think in your question is the reason why I wanted to have this conversation with you, having read your book about Sun Ra, and other things that you’ve written and said. Is there something magical? On one level nobody should have that text in their head, something’s not right, it hurts to fit that in my mind, to feel like I have to put this down on paper, to read it, to say it. It’s not right, there’s something broken there. And maybe what you’re suggesting is that — maybe I’m getting a little out my own field of knowledge — but that occasionally in the broken mind is the ability to summon forth something that makes sense.

TS: The two together are just amazing to read, one against the other. ‘I call upon all the words, all tongues, all languages, all the numbers.’ I think you’re really getting back to that idea of whether or not this is an escape valve for dissent, something permitted, something tolerated. I don’t want to play devil’s advocate, but I want to just reformulate the thought experiment, and see if you can see it from this angle. Well of course it is. Of course it is just that. That if the avant-garde work, if the exceptionalist work, the work that isn’t, you know it’s not pop music, it’s not a mega-rap, it’s going to be consumed by an audience that holds it quite dear, and isn’t concerned that it isn’t caught up in that other discussion, where things are measured in record sales, and numbers of stadiums that you can sell out, et cetera. So this work exists and I think if we allow it to be, it is just that, it is just an escape valve for surplus intelligence, surplus critical perspective, brilliant people that need something to do. And here you are, get yourself a micro-label, and an audience and a facebook page and go for it. Or, I think you can wade into these waters where responsibility is front and centre, and assume that without some exceptional deliberation as part of your process you will arrive at something that only creates a very small self-contained circuit and does not create that opening into possibilities that I think the force of your work implies.

You know there’s a sense that the way everything is coming at you, you’re not permitted to be neutral. You’re going to take sides, and you don’t want to be on that other side. Who would? So then you have to say what’s really being critiqued about what I’m attached to and how I identify myself, and I think anyone could look at it and say ‘yeah, I’m over here too.’ Like you said, it points at all of us. So, I’m where you’re at. My youngest child is five…

KN: Like mine.

TS: …and you know, they don’t deserve this world. They don’t deserve this shit. This should be over. This is like a rerun. It’s time for it to stop. You see, I think this is what’s beautiful about the virus, and I know the virus has hurt a lot of people and inconvenienced everybody. Killed people, good people. I know that. But the virus has also shown that it is possible to affect the whole thing at once. The whole thing can be turned off. When you’re talking about shutting down a country like India, you’re expressing some possibilities there, you’re expressing some possibilities that all this stuff, and when money is needed, you know these assholes can shit out trillions of dollars.

KN: Yeah.

TS: Here you go! So, we’ve seen these large-scale interruptions in business-as-usual through the lens of this pandemic. And I just kind of think it’s time to use art to act like the virus, it’s got to get under people’s skin, it’s got to be contagious. And that’s not the same as popularity. It’s just got to be there whether you like or not, it’s got to be in your face. I’m interested in your perspective.

KN: Well you said a lot. One thing I can pick up on, in this culture, the cruelty is the point. Because yes, they can shit out trillions of dollars if they need to, and they’re still not doing it, how they should, but they could, and they could still be perversely comfortable. Those who can afford to make the decisions and part with trillions of dollars could do it without noticing it, and that’s how I know that the cruelty is the point. And that’s why no fate is too bad for them. You know? I’m fucking furious. Like you said, I have a five year old child, and he’s a beautiful child, as all five year old’s are! He doesn’t deserve this shit. And you don’t deserve this shit, because you were somebody’s five year old once. I go back to the Litanies of Trees, and every time I go back to it, I’m in tears, I can’t handle that piece. I can’t handle it. It is, like I said, it’s a piece that intentionally balances out the tone of the first piece, the Elegies.

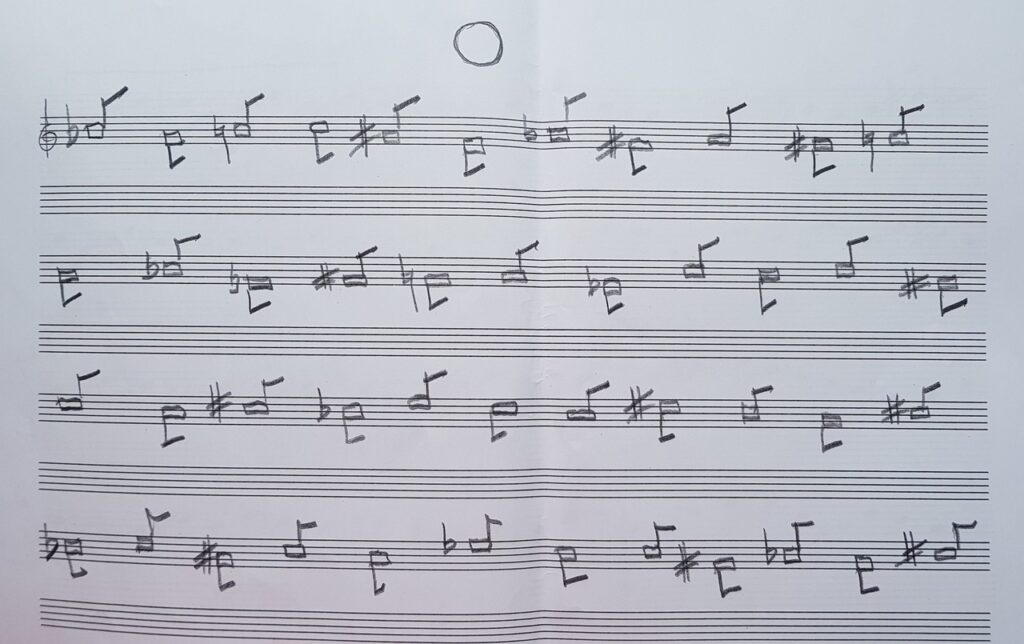

Litanies of Trees & Deep Biographies

TS: Look at what you’re doing, upholding the morality of trees against the immorality of empire. It’s really beautiful. The symmetry of it is beautiful. ‘Trees that outdate empires, successions of empires. Trees many times older than the language I speak.’ That’s just beautiful.

KN: So you know, I moved, after writing that piece. I moved from Philadelphia to upstate New York. Steps from my house there’s this beautiful wildflower preserve where I go walking with my kid. That’s where I recorded the bird sounds in Litanies of Trees. Steps from my house. It’s a total cliché to go into the woods and to think of it as a temple because to describe it that way, all of this is about me — but it’s not about me. That’s a really beautiful feeling too. When you’re in the world, when you’re in the shit, the only way to get by, is in some part of yourself it’s got to be about you. It’s about the cash in your pocket, or not in your pocket, right? It’s about approaching someone on the street and ‘is this a friendly or a not friendly interaction that’s about to take place?’ In the pandemic era there’s another level, which is: ‘is our social practice, our appraisal of public health similar or not?’ The two people who are passing each other on the street, do we value human life in similar ways, or in drastically different ways? Including each other’s lives, right? Those are negotiations that take place, and so on some level it’s always about me. It has to be.

TS: Or you’ll perish.

KN: Right. You go into the woods, and it’s not about you, it’s not about me. And there’s a release that I feel going into the woods. Even describing it to you now I feel emotional.

Keir Neuringer's sketch book, with the notation for Litanies of Trees

Keir Neuringer's sketch book, with the notation for Litanies of Trees

TS: All my favourite people are trees! I know exactly what you’re talking about. There’s a tone to the music in Litanies that’s consistent with the tone that’s in the emotions that are being conveyed in this inventory of loss that we start the album with. The opening text is an inventory of what’s been turned over, what’s been spilled out. So, the music is beautiful, but it’s in that tone, it’s in that space. And yet, the remembrances of the trees that populated your childhood, I don’t want to say it resolved anything, but it did give me hope, it did make it a hopeful piece, it did bring some light there, and even joy. Even if it wasn’t joy in the present tense it was joy that was very valuable through your memories through your relationship with the woods that you remember as a young person.

KN: That text, that section of the text where I’m talking about the trees from my childhood, it’s so mundane. It’s so beginner’s mind. I grew up in the suburbs outside of New York City. There was this backyard. You walk out the back of the house and to the right there was a Japanese maple, a beautiful tree. And then right in the centre there was a dogwood. And to the left there were two or three big sugar maples (depending on what year we’re talking about), and there was an old cherry tree in the back, and the back of the property was lined with these red cedars. They were all so distinctive, like characters. One tree had the tire swing. Another tree didn’t have the tire swing but was easy to climb. Another tree had to come down at a certain point. Another tree, someone was badly hurt trying to cut a branch down, I was like five years old, and it etched itself into my memory. All these trees have very strong…

TS: They have biographies.

KN: Yeah. Deep biographies. And I didn’t want to go into that. I just wanted to say that I remember them. That they existed.

TS: That’s very honourable though, that’s the kind of empathy it’s going to take to get us over. You know we’re so broken apart that it’s almost like cross-species communication. And acknowledging that, rather than glossing over it, would help us follow through and get where we need to get rather than being frozen. Because we expect it to be far easier than it’s really going to be. It’s going to be hard, but you’ve got to start it to get it done, and if you’re just kind of waiting for it to get easy it’s not going to happen.

KN: I like the way you put that.

Optimism, Imperialism & Alter Destiny

TS: I’m tremendously, in a weird kind of way, very optimistic, because I really do think that things are falling apart. And that the good stuff is on the other side. The good stuff, the stuff that our children actually deserve, my faith is not in America. My faith is a slave’s faith. Someday master’s house is going to burn down, and I’ll plant a nice little field in the ashes. And I’m just anxious to see what it is, and I know it’s going to take a lot of hard, responsible work to keep whatever shakes out of all this chaos from being just an extension of the nightmare, but I’m ready for that, and this kind of work is not peripheral to that preparation. It’s a part of it. It’s a part of taking on the responsibility of ‘oh, we have to redo all of social order all at once.’ Well that’s a lot! You know?

KN: Yeah.

TS: ‘Do you need any help?’ You know? ‘Do we get any help?’ That’s a lot. Come on now. But we have to fix this. We have to figure out the social-political-economic crisis so that we can get all hands on deck and put the fire out, because the planet is on fire. We’re in it, and it’s burning, and we’re not dealing with it because we’re at each other’s throats trying to make money. So I just, like, see around the corner, I see something that’s like a global Arab Spring, mothers and fathers and people that care about children and trees saying ‘we’re not doing this anymore’, we can get up from the table when we have remembered how to be decent to each other, and we can restart, and we can do it a whole different way.

“It matters who's saying what and where they're coming from when they say it.”

KN: There’s something there in what you’re saying. Something that I think about that relates to Elegies. It gets somewhere that might be dangerous and not dangerous in the good way, which is — and this is not a new idea — the world, not just in a metaphorical way, but in a literal way, can be destroyed many times over by very few people who have shown themselves willing to do it. There’s a totalness of it, what I say in my description of Elegies, I can’t be specific. I’ve written a couple of elegies before, that are very specific, they monumentalise something very specific. But here I just can’t, you know? The problem for thoughtful people is that the response to the position we’re put in has to be also on a grand total scale. And yes, on a tactical level I agree, like, global general strike. Yes. But on another level, the impulse to be total and global is…

TS: Is imperial enough in itself?

KN: It either leads to imperialism or nihilism. I’m thinking of the impulses described, I don’t know if you know Albert Camus’ The Rebel?

TS: Sure.

KN: Reading that book helped me back away from certain notions that I had about what is to be done. And I hold these feelings as a paradox. And I sit with them all the time. On the one hand, what is to be done is total, and on the other hand, you can’t do total. But I can do this, what I’m doing. That’s why I say that the optimism of the work is in the doing of it, with other people, for other people, for you to hear. That way I feel myself part of something. I’m not asking of myself to figure it all out. But to be part of something.

TS: Or a component.

KN: Yeah, be in the flow, that leads to this positive thing that you’re describing. And again, this is one of the reasons I wanted to have this conversation with you specifically. It’s because you describe something in your other work, something that is inevitable and is already happening. And I hear that, and I ask myself to find that. To be in the flow of that, you use the term ‘alter destiny’.

TS: That’s Sun Ra’s term, yes.

KN: I’m asking myself to push towards that. We started this conversation talking about gloom, right? And I responded to you that maybe in times like these we’re called on to do something that presents joy when it doesn’t feel like there is much. It matters who’s saying what and where they’re coming from when they say it. I think that the scene that you roll in, the community that you roll in, where things spring from, it matters. It’s not benign. And I think sometimes people who want to push back against identity politics, for example, they’re missing that.

TS: I think that’s important — trying to work that through my own realities in this work. It’s really good Keir, bottom line, it’s really good. And Ensemble Klang, it’s a really nice setting for these ideas.