Pete Harden’s Precious Metals

Oscar Bettison interviews Klang’s guitarist and composer Pete Harden on topics surrounding his album of works for Ensemble Klang ‘Precious Metals’ (EKR07).

Oscar Bettison: Can you name ten pieces that have changed you as a composer?

Pete Harden: That’s a difficult question. Partly because for my work as a programmer and performer with Ensemble Klang I surround myself with the music and composers who I feel are significant – people who are working on challenging, profound, progressive, beautiful, grotesque, and sometimes beautifully grotesque music – I couldn’t (and wouldn’t!) keep asking composers for new works if I didn’t love what they do. So I’m constantly in dialogue with composers and music for which I have a great passion – and I can’t suggest that my own music remains unaffected by that dialogue. In that regard, all the composers I’ve worked with have ‘changed’ me somehow – but in addition to all those pieces and composers I can still add a good few.

Most interesting for me now are the works that are slow-burners, pieces that I’ve known for a long period, and yet only recently realised have had such a considerable effect on me. One of those would be Movement Within by Glenn Branca. I heard this live on the radio, while still in the UK, in the 1990s, played by the Bang on a Can All-stars at the BBC Proms, of all places! And if they hadn’t have played at the BBC Proms I might never have heard them, and might never have heard of Glenn Branca. It must be one of the craziest, most unfathomable works to have been performed at the Royal Albert Hall, at that venerable festival of classical music. They played a fantastic program, but this work stayed with me, because I just couldn’t figure out what on earth was happening! I had no idea what the rhythmic material was, or the harmonic material, or even what some of the instruments were. I had no idea what was on the page, or what I was supposed to be listening to, or what I might be supposed to be feeling. And the work totally entranced me. It was the first time I realized that music didn’t have to be familiar or comforting – great music could also be demanding and enigmatic. It was a moment in which I also saw that there were daring and adventurous performers passionately and brilliantly communicating that music to an audience. Hearing it as a teenager led me down a path (from Bang on a Can to Steve Martland to Louis Andriessen) that brought me to the Netherlands.

Ensemble Klang playing Precious Metals at Rewire Festival 2017, with visuals by Vincent van den Broek

Ensemble Klang playing Precious Metals at Rewire Festival 2017, with visuals by Vincent van den Broek

So then we have to add De Staat by Louis Andriessen. I could have almost any of Louis’ works on this list, and yet I think I must have heard De Staat before any of the others. I remember rewinding a cassette tape to listen to the trombone section over and over again, wondering whether you were really allowed to do something so raucous and physical in ‘proper’ contemporary music.

And also then Trance by Michael Gordon, which I would have heard in the Icebreaker ensemble recording on the Argo label also in the 90s. Aside from the fantastic musical qualities, conjuring this ecstatic energy from the get-go, and maintaining it, and structuring it, across fifty-five minutes, it was something that brought together what had for me, up till that point, been two totally separate worlds: one of serious contemporary music, and the other of a sound and instrumentation rooted in popular music. As an electric guitarist I was playing in bands at the weekends, and as a composition student I was studying Boulez and Birtwistle during the weekdays. Suddenly I heard this piece, and I realized that there was of course a third way: it was absolutely possible to be making significant and important music for the concert stage that also uses the soundworld and instruments that we associate with pop (or rock or jazz or whatever), and that was the soundworld in which I was so immersed and in which I felt so at home.

As a guitarist I didn’t get to play in orchestras when growing up, so I didn’t naturally navigate towards an orchestra when I sat down to compose. I even think the first piece I played in a conducted chamber ensemble was Boulez’s Eclat, which is wonderful, but you can see that as a guitarist you don’t get much of an opportunity to live and breath chamber ensembles, let alone orchestras. So Louis Andriessen, and Bang on a Can and Michael Gordon were all eye-openers for me at an early stage.

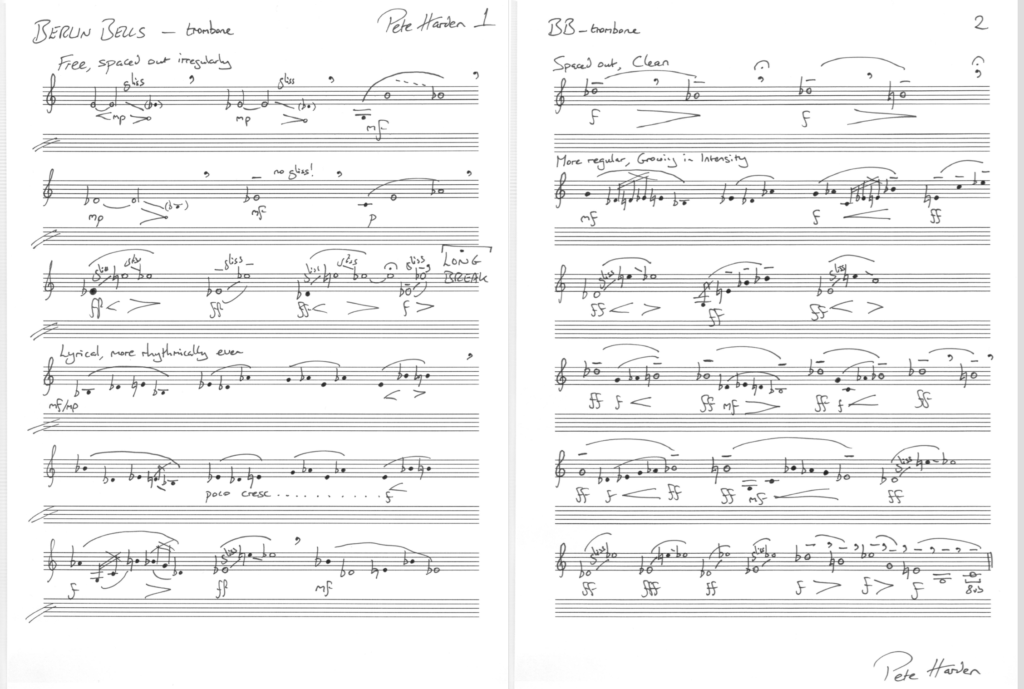

Berlin Bells (trombone part) - Pete Harden

Berlin Bells (trombone part) - Pete Harden

“Ben Johnston’s String Quartet IV was my gateway drug into the world of just intonation and microtonal music.”

After arriving in the Netherlands in 2000, while studying with Louis, he insisted I went to meet Richard Ayres. And we get another piece on the list, Richard’s No. 30 (noncerto for cello, soprano and orchestra). It was one of those moments where I heard something the like of which I’d never heard before, and it broadened my understanding of what music could be, the endless possibilities. I wasn’t only floored by it, I loved it as well. It’s a magnetic, warm music that also says something new and profound. Richard then became an important teacher for me, someone who asked all the difficult questions at all the right times.

So having promised to not put any Ensemble Klang folk on the list, I do have to include Narayana’s Cows by Tom Johnson. The piece is a musical demonstration of a mathematical problem, and what I think is so original and strong is the way in which, as a listener, you are brought in to the architecture of the piece. You’re brought in to understanding the reason for the existence of every note, what each note means. In a way, it’s the documentation of the construction of a piece of music. So as a listener you’re hearing notes differently to how you hear notes in other pieces – you listen as a builder, understanding the logic behind each new pitch, new rhythm, and new chord. It got me started on Information Aesthetics, and musical or sonic representations of data, which I find fascinating and beautiful. There’s lots of research in this field now, into things like whether we can hear patterns in data quicker than we can see it visually, but in my case I was particularly interested in using data compositionally. I made a number of works in that area, such as Population Pieces (2009) which is a composition that auralizes the changes in the Dutch population through the 20th century.

Next, I have to throw in Ben Johnston’s String Quartet IV, as my gateway drug into the world of just intonation and microtonal music. I adore the piece for how its exquisite composition transcends its traditional materials (a theme and variations on Amazing Grace) – it’s a piece of real beauty and ingenuity. It’s new and conceptual and yet rooted in traditional music too.

“the Gnossiennes achieve something amazing, a sort of musical magic, a transcendence”

There are two works I can add for contrary reasons: Paul Termos’s 1991 is a work for trio (saxophone, piano and percussion) written for the Loos Ensemble that strips away any excess, any ornamentation, anything unnecessary, to extraordinary effect. The composer lays everything bare – you don’t so much hear the nuts and bolts of a piece, but are simply presented with its outline. In this work about proportion, structure, and scraps of material you also get treated to one of the best and maybe most unsettling (and funny) endings.

And then the counter-opposite of the Termos might be Fausto Romitelli’s Professor Bad Trip a journey into excess and opulence, of overindulgence and luxury. What I find fantastic about this work is that its roots in spectralism don’t dominate what the composer is dealing with: the experience of the listener. How are the listeners feeling at each moment, what effect is the music having on the listener, how is the experience of time, and comfort, being controlled? The work creates its own unique world. And I put it in here also as a representation for me of how many of the greatest works of the 21st century are now scored for smaller chamber ensembles – with amplification and electronics, and with excellent (and demanding!) instrumental writing, smaller instrumental line-ups can conjure an equally expansive, thrilling and varied sonic world for which 100 years ago we would rely on the orchestra.

One more luxurious piece would be Olga Neuwirth’s opera on David Lynch’s Lost Highway. In a funny way it’s not so far removed from the Romitelli. The music has this incredible pacing across the whole duration, and music seems simultaneously familiar and yet also alien, that careful balance creates the unsettling feeling that nothing is really what it seems. It’s a work that through its own strangeness deals directly with humanity.

And the last one is the oldest one (it’s still not very old!). Yet it has only recently struck me, and that’s Erik Satie’s Gnossiennes. As a musician, or composer, maybe particularly as a student, I was often most intrigued and impressed, gripped maybe, by the pieces that I heard in which I couldn’t figure out how a composer had achieved something. You find yourself admiring a piece for the simple reason that there’s something new in it, and you have to investigate how it’s done, or what it is (it could be sounds, structure, concepts). With the Gnossiennes you can hear very clearly, or figure out quite quickly, the nuts and bolts of the pieces, and yet they achieve something amazing, a sort of musical magic, a transcendence – it’s the factor every composer and musician is looking for of course. Maybe it’s a case of not looking closer but taking a step back from them. In any case, I’m currently fascinated by works that have that beguiling quality, works that transcend their own material. A topic I suspect I’ll be busy investigating for the rest of my life.

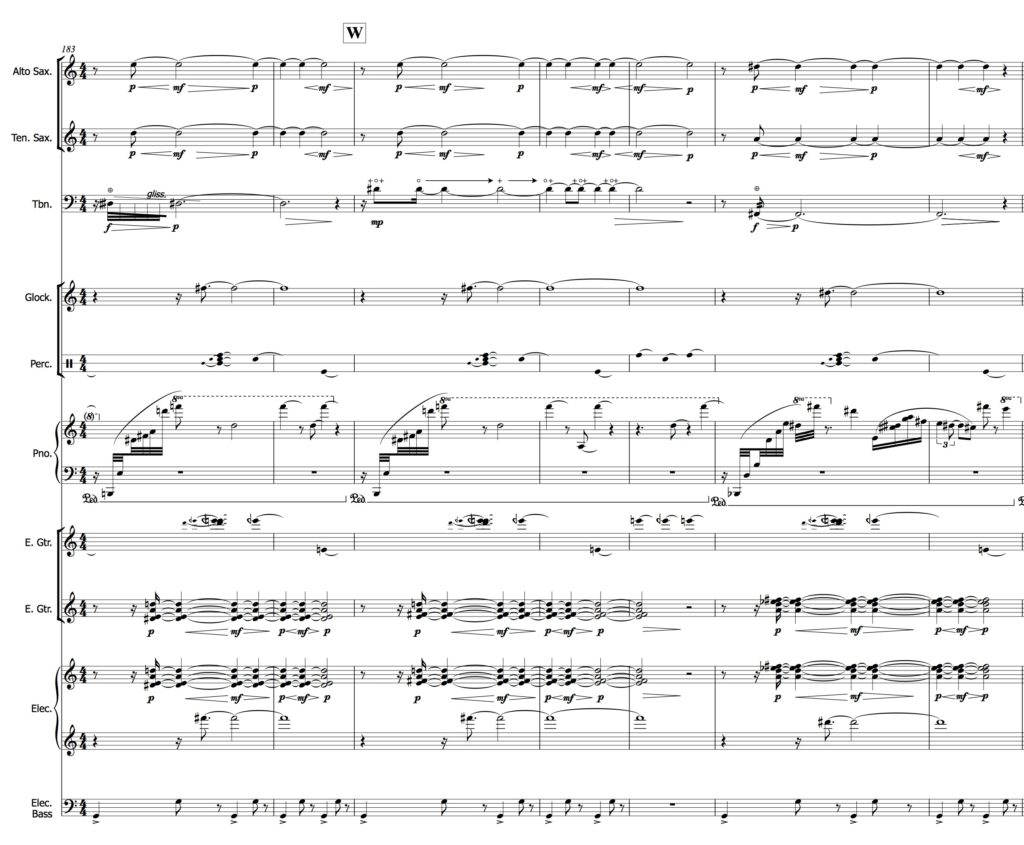

forming a petal from a piece of metal (score excerpt) - Pete Harden

forming a petal from a piece of metal (score excerpt) - Pete Harden

OB: Sculpture, Visual Art, Material

PH: I’m really inspired by visual imagery. With many of my pieces I have a strong visual image in my mind, not always a work of art, or specific objects, sometimes just a sense of colour, form, or a sense of place. But there is never a concrete explanation for how those images relate to the music, they’re not translated or encoded. For example, for an earlier work of mine, two slightly broken contraptions (2005) I simply had this vivid picture in my head of two clocks, stranded in the middle of a desert, fallen out of a plane, or off the back of a truck, laying in pieces but occasionally still ticking. That use of imagery also works as a reflection of my strong interest in non-developmental forms – I want my pieces to just sit there, as much being navigated by the listener, observed from different angles, as pulling the listener along on a journey. They’re like a picture hanging on the wall. So the use of non-developmental forms is also about not wanting the music to control the listener in any way. I want the listener to take a step into the piece.

Having said all that, there are a few visual references that provide important inspiration for this album. Two visual artists that triggered me are Fiona Hall and Richard Serra. In Richard Serra’s huge rusted steel sculptures, works that deal with symmetry and scale, strength and deterioration, you’re brilliantly drawn in by the outer solidity, and formal clarity, while wanting to touch and feel and smell these metal plates to sense their materiality and aging. That ability for the experience of the work to be different from a distance than from close up is fascinating. What I’d hope for in these musical works is that they have a simple outer structure, or foundations, and yet there’s space within that for a sensuousness of sound to be experienced.

Serra’s bringing of those industrial materials into art is also (in a very different way) shared by Fiona Hall. She has a series of works made from sardine cans, the metal intricately sculpted into flora and fauna that sprouts above the tin from an equally intricately sculpted erotic image placed inside the tin. It’s such a striking work, inviting closer inspection, to peek inside these little tins. But it also talks of materials and recycling, and our human relationship to nature. It combines mass-produced materials with man-made objects and organic sculptures. That was a big influence on Forming a Petal from a Piece of Metal, the title of which relates to the Hall works, but also to the metal of our musical instruments, with this idea of things like the saxophones as metal lungs. The repetition in that work relating to this mass-produced vs man-made theme, they’re repeats, but because we’re performing them they’re not exact repeats, it’s always changing, and then also the repeats take on a life (and scale) of their own.

OB: Big Ideas and Abstract Concepts

PH: Yes to both of those! I’ve always been interested in constructed music. Maybe coming from a mathematics background meant that I was always happy to have a reason for the notes being where they were. But I also want those sounds to have a sensuality to them – music is about humanity. So sometimes the foundations are laid first, and the musical material filled in – that occurred in a lot of the Information Aesthetics works that I was busy with. And with Precious Metals, often the musical material came first, I wanted to let it breath on its own, sing a little, and then the foundations had to be filled in afterwards.

In terms of ‘big ideas’, for a while I was interested in these monumental projects – I did a piece for four cars and large ensemble, and had plans to try and do something with buildings – fortunately at the moment I’m working with ‘big ideas’ articulated through much smaller forces, which is of course much more practical.

The idea of music as research, or sonic exploration, or experiential exploration, is something with which I strongly sympathise, so abstract concepts are really important to me. I like music that’s enigmatic, that as a listener you’re not always sure what it’s asking of you.

But sometimes those ideas can surface and become concrete references, ways to interpret a piece – that can also be fine. So ideas of recycling material in this album are really important: some works deal with that on a conceptual level (Guiyu Guitars) while some are the result of musical material that I’ve reworked and reworked through different pieces over many years. (The harmonic material in Forming a Petal I sketched in 2005). And on a surface level, the almost over-use of delays in all these works is also a representation of recycling and repurposing.

OB: Popular Music and Technology

PH: I touched on this quickly above, coming as a guitarist out of that performative world, my roots lie working within the sound world of pop music. But what I also love about the pop world is the ‘do it’ aesthetic, not just in relation to music-making but also lo-fi electronics: work with what you’ve got to hand, grab some gear, start playing, see what it sounds like, and adjust it accordingly. There’s much less talking or philosophising than in the ‘contemporary classical’ music world, which can only be good! Like Louis Andriessen said ‘No one ever became a good tennis player by simply talking about playing tennis’.

“I think of each of these pieces as a plate or surface, intended as sheets of metal that hang there, non-developmental”

On a more conceptual level, technology and pop are represented on this album by Guiyu Guitars, which is a piece purely for guitar pedals (well aside from the guitar chord played right at the beginning). It’s a work about the pedals themselves, and the metals used within them, and their circuit board. Guiyu, in China, is a huge electronic waste recycling site. There’s a river running through the city, which is now massively polluted, and I imagined the pedals, and the music they’ve carried, arriving from upstream and emerging downstream, post-processing, with key elements stripped back and, while ready for a new purpose, they still hold the memory of music past.

OB: Form and Development. Does Steel Wounds & Beaten Sounds have a climax?

PH: I think of each of these pieces as a plate or surface, or a number of plates. They are intended as sheets of metal that hang there, so in a classical sense they are non-developmental, but as you move across the sheet it’s always changing and you’re always experiencing a different texture or colour, or imperfection or impurity. One of the underlying themes of the album is re-using, recycling of materials, with metals we dig it up, process it, make something, melt it down, and make something new.

Those plates are each constructed with layers of material, or with different compounds. So some of the works are single sheets of material (Forming a Petal and Berlin Bells). With the two movement work, Guiyu Guitars Upstream represents a single sheet of material that then gets re-smelted or recycled into a companion piece Guiyu Guitars Downstream – the first movement is a sort flowing organic object, and the second uses only fragments from the first, repurposed. So the whole piece is recycling and re-processing this original chord, turning it one way then the other, twisting the new object again and again.

And then Steel Wounds & Beaten Sounds is a piece that’s made up of multiple plates (four, each of a slightly different dimension). Those plates are jointed, or unified, by the keyboard patch that runs through all four – there are fixed rhythmic delays in the keyboard part that form a simple sort of architectural mesh upon which the musical material sits. One of the compositional problems I was trying to address in the piece was how to create something that’s rhythmical diverse and changing even when there’s a fixed pulse or ‘ticking’ all the way through. I use the ‘mesh’ as a building block upon which I hang material. That keyboard is also tuned to a Just Intonation scale with lots of versions of 2nds and 3rds, multiple ‘blue notes’, which colour the chords. So indeed we hear the last section of Steel Wounds as a sort of climax, but that material is also just static, it’s just another plate, maybe simply a brighter colour than the previous three. But I’m aware that it has the feeling of a climax, so I cut that section off a little earlier than you might expect.

Ensemble Klang playing Precious Metals at Rewire Festival 2017, with visuals by Vincent van den Broek

Ensemble Klang playing Precious Metals at Rewire Festival 2017, with visuals by Vincent van den Broek

OB: The score vs. performative practice. Control. How does being a performer and member of your own ensemble influence your music?

PH: One of the pieces I didn’t mention in the ten pieces above was Heiner Goebbels’ Walden, which we worked with him on, and later also released. That was a hugely informative project for me, observing how he worked with performers, and how he treated what was on the page in comparison with how he then crafted sound in the space, with the players themselves. Since then, I’ve been quite stringently stripping away anything non-essential from the pages of the score. Not to give the performers space to improvise, but to give them space to be musicians. I think the job of the notation is to communicate what the subject of the piece is as economically as possible, so that the musicians can embody that piece on stage. Of course the notation varies according to who I’m working with, and what the structure and nature of the rehearsals are. But with Ensemble Klang I obviously have an incredibly luxurious working environment – knowing everybody so well, and having played with them for so many years.

On this album Berlin Bells allows the performers a lot of freedom in timing – everyone has their own part, which is seemingly un-coordinated. But in fact that freedom simply allows the musicians to use their ears, respond to the music that’s happening around them, respond to each other. And built up through a number of rehearsals, the coincidences within each part in fact ended up occurring exactly where I had intended them to occur. Notationally, it represents something that I’ll continue with in the future in working with the group. The piece is a solo for our trombone player Anton van Houten, and it also uses the tubax (a contrabass saxophone) that our saxophonist plays. Obviously it helps that those rehearsal and working practices are shaped by us ourselves, but they’re transferable, as is the piece, to any group of performers or players.