Q&A with Peter Adriaansz

Pete Harden interviews Peter Adriaansz on topics surrounding his album ‘Waves’ (EKR01), recorded and released by Ensemble Klang in 2010.

Q. I thought I should start by asking about your upbringing, it strikes me that it has an important part to play in the music that you write. You lived in a number of different countries when you were growing up although you completed all your musical studies in the Netherlands. Do you think of yourself as a ‘Dutch’ composer? Your music has strong allegiances to the American experimental tradition – did growing up there instill some of this in you?

A. Well, only the first eight years of my life were really spent in hectic intercontinental travel, but it would be impossible to underplay the residue of my earliest musical memories, which consisted of a strange mix between Benjamin Britten’s Serenade, Raindrops keep Falling on my Head, my mother playing tabla and singing dhrupads while my father practiced Rameau on the harpsichord. To a certain degree this transience of cultures has certainly marked me and fueled my artistic choices in life. In any case it instilled in me a deep respect for other cultures and a fascination for the origins of music, a period before historical development and communal syntax ‘polluted’ it so to speak. Though educated – pretty strictly – within the Eurocentric line and its set of values, I nonetheless always maintained a healthy skepticism towards the Western classical music tradition, which all my training deemed me to stem from and embrace. I guess for all these reasons I’ve also always felt skeptical about concepts of shared cultural identity.

Most of the music on this CD definitely falls outside of the realm of what could typically be regarded as ‘Dutch’ music. So in that respect, no, I can barely consider myself a typical ‘Dutch’ composer anymore. I think most of my colleagues would agree! It’s obviously much more closely linked to specific North American developments, made over the last fifty years or so, in the areas of tuning, micro acoustics and so on. I was never trained in the States however.

Incidentally, regarding this issue of ‘Dutchness’, a trait which is most certainly definable, I would like to point out that the 20th century in Holland produced two (not one, as is commonly thought) significant contributions to musical thought. One would be the line of the The Hague School and the other, the ideas forwarded by Ton de Leeuw. If I had to affiliate to any form of ‘Dutchness’ at this moment, it would be to the latter – a way of thinking which at least carries in it a potential to transcend.

'What I listen for in music?' is simply: concentration.

Q. Why are you a musician? What do you listen to music for? What does it bring to your life?

A. The shorter the question, the harder the answer! ‘Why am I a musician’…? No idea! I was born that way… There never was any real choice in the matter. ‘What I listen for in music?’ – if you don’t mind my altering your question slightly – is simply: concentration. Concentration of concept, concentration of execution, plus the appropriate choices. No unnecessary obscurities, avoidance of clear topics or dwelling/commenting on, or through historical lineage: I don’t like being diverted, entertained or having games played with my so-called collective conscience. Neither do I truly believe that that’s what music is really about. Although I’m well aware that I’m in a vast minority with this statement.

What I bring in my own work is a very specific element of music, which it is no less important for me to research than it is important for me to impart to others. What it brings to my life is insight into something which fascinates me deeply, but more importantly raises more and more questions about the nature of music the deeper I go. I guess, just doing all the research is something which fills me with a feeling of discovery and thus keeps music alive to me – as an autonomous art, free from dialectics. It’s truly something I can believe in.

Q. On the disc we have a near-complete set of your Waves pieces, there are 13 in total. Waves 1–4 are for solo piano, represented on this disc by Wave 3. What happened to Waves 8–10?

A. Half-finished. When the original setup for what was initially Waves 8–10 fell through I had to suddenly come up with an entirely new work, which became the present #11–13. Waves 8–10 lie in a dormant, half-finished state, from which I wonder if they will ever be woken. They were intended for a much larger setup.

The whole series of thirteen were imagined as a continual two-hour series for two smaller setups, full-range and treble, and one larger setup, with the four piano pieces at start, end and in between.

(A propos, my works-list has a few more of these ‘dormant’ pieces, like Anekabahudaravaktranetram – a 90 minute work for large orchestra and voices; written off the cuff or together with another commission but then waiting for concrete demand and the necessary time in order to finish them!)

Q. You use EBows in the piano for much of this music – they create this beautiful, very ‘un-piano-like’, sound. Electric guitarists will already be familiar with them but recently EBows have gained popularity in the contemporary music world, especially in piano writing. Can you tell us a little bit how you first came to use them?

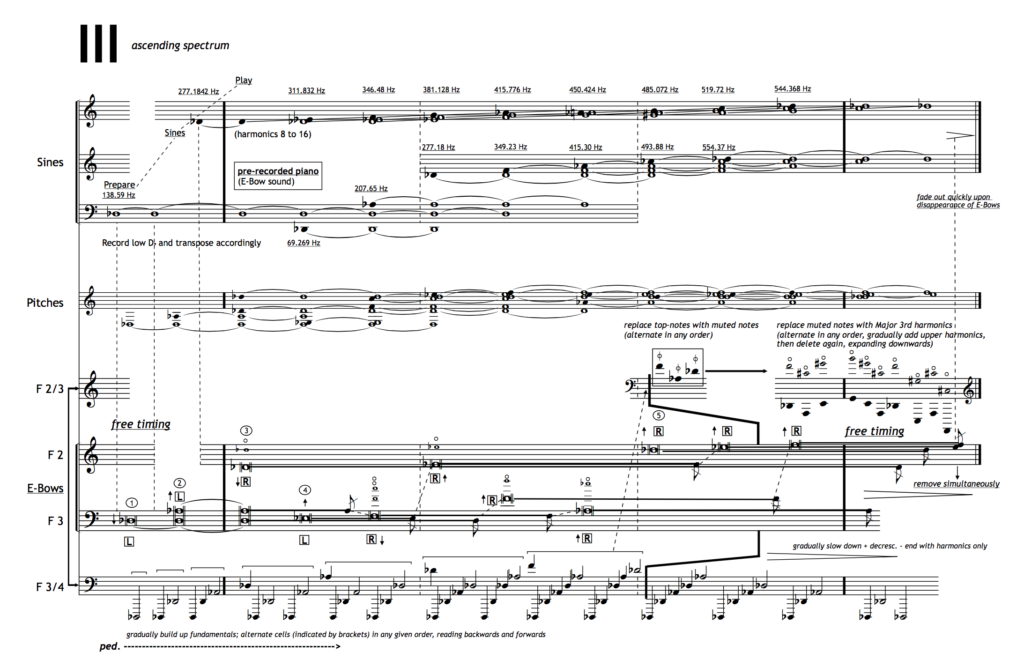

A. Well, I think the first time I used them was in Serenades II-IV (2004), for electric guitar quartet. The first time I heard them used on the piano is when I heard Cor Fuhler use them in one of his pieces. That was somewhere around the time I was writing the Structures. Considering the nature of that music I immediately knew I had to use them – initially for matters of their pure, eternal, sound. Later, when writing the first of the Waves series, I started experimenting with multiple EBows. By that time I had started to use them more for purposes of vibration and to conjure up ‘ghost harmonies’. Eventually I settled on five EBows, prepared by widening their bridges and filing away the contact surfaces to about half of their height. With these five I found I could adequately cover what I needed – the usable range is not that large after all. A lot of their use had to do with doublings and combining the overtone-switch with the fundamental switch, used both in front as well as behind the hammers. I found that certain combinations would inevitably lead to magnifying the harmonic spectrum and creating all kind of internal beatings. Anyway, a lot of research went into their use, which tends to make the piano parts in many of these pieces quite virtuoso in fact. Wave 3 for example is a case in fact, where the pianist needs to combine struck pitches, muted pitches, bell-harmonics and muted harmonics with the continual re-positioning of the five EBows, using both left and right switches – and then vary all of the material continually while listening to the sine patch as he/she proceeds. Trying to create one continuous, seamless, flow of different activities and then blend them all together in an organic way can sometimes be horrendously difficult! But Saskia has proven herself to be a master at this. She does it with an exceptional refinement and sense of timing.

Saskia Lankhoorn performing work by Peter Adriaansz

Saskia Lankhoorn performing work by Peter Adriaansz

“In painting, those that come closest to what I admire are people like Mark Rothko (of course) and Jackson Pollock.”

Q. The only ‘non-Wave’ on the CD is Nu descendant un escalier which you wrote for Klang’s ‘Principles of Concision’. This project asked composers for their ‘signature’, a work which in as brief a means as possible articulates their compositional identity. I felt especially mischievous in involving you because your works were tending to the extreme in duration yet this demanded real brevity. In the end you came up with not just one short piece but three! It’s title comes from a Marcel Duchamp painting – do you frequently look to the world of the visual arts for inspiration?

A. No, not really. In all disciplines there are people who inspire me with their ideas. Duchamp was one of them of course. In fact I find it’s often more the ideas that do it for me than the actual concrete products! All art is simply that to me: an expression of an idea, and in this I see no difference whatsoever between the various disciplines. In painting, those that come closest to what I admire are people like Mark Rothko (of course) and Jackson Pollock. I find that both infinitely transcend the medium and were also consciously seeking for ways to do so. ‘Ideas’ are big things in both cases! Yes, I completely understood the mischief of your request! But you forgot that I’d done all kind of different things up till that point – including the writing of brief pieces! Although I really couldn’t term it a ‘signature of my (present) identity’ – that’s simply impossible when ‘sound-duration’ is one of the base parameters – it does cover a few of the features in its fluidity of sound and how it deals with tempo relations for example. It’s just kind of sped up, pulses become rhythms etc. Incidentally, the title came as a bit of an afterthought, when I realized the piece was consistently descending in register. That little ritual reminded me of the image of this fractured lady descending the stairway in a kind of slow motion – moving, yet frozen at the same time. Talk about motion on a flat surface, that’s one vibrant painting!

Q. You have developed a very precise musical notation, I suppose since the first Structures (2005), for these ‘long-sound-pieces’. On the surface it can appear as though the performers have a lot of freedom, indeed I think one of the strengths of your notation is that it makes the performers feel like they have a lot of freedom thereby opening their ears and heightening their sense of listening, but in fact the works exert very close control over the events within. I remember talking to you after a performance of Triple Concerto (2003), and you said that you had wanted to write a piece with a simplicity of notation but found in the end that the composer in you could not resist controlling more and more aspects of the piece. I wonder now, how do you decide what gets notated and what doesn’t? And also how far back in your work does this struggle between balancing, let’s say a ‘perfection’ in the notated work and making sure the performers do exactly what you want?

A. This is probably the hardest question of all, since it touches on all kind of cultural and even political choices, besides lying at the root of the famous canon that ‘the greatest freedom comes with the greatest severity’. This is definitely something I’ve been battling with for most of my creative life, all the way from Music of Mercy (1995) onwards: the idea of ‘not having to do anything in order for something to happen nonetheless’. Also, the idea that the greatest beauty is that which is left alone, without human interference – after all, the less one does the closer to some kind of truth one can come. At the root it really is an ethical point, pertaining to the whole topic of ‘composer manipulation’, ‘ego’ and so on.

To cut it short though, my conclusion – especially over the last five years or so, where the notation has really taken on a guise of its own – has been that all revolves around notation: every kind of music at root demands its own notation. In that regard, the codified notation we generally use can really stand in the way of music’s freedom to sound – and determines much more of the eventual result than we often like to think. Especially in the area of sound, the compositional ‘intention’ which is implied and encouraged in common notation can be a truly fail proof way of killing it the very moment it appears! (Just try this test: listen to nearly any example of contemporary music and then measure the amount of time between the first event and the second, this says everything about whether the piece is based on sound or on pitch.) So, in order for musicians to really listen and carry responsibility for their part in the whole, the notation must enable their ability to make ‘on the spot’ choices. This basically means that, within the framework of a desired sound and form, the musicians are given as much freedom as possible for them to be able to influence the environment. In Waves 5–7 for example, where the musicians are given space to select both pitches as well as entries, this freedom is larger than in Waves 11-13, where the periodic entries are simply set, in order to guarantee a certain pacing and the presence of silences. The hardest part of this procedure probably lies in the endeavor to build up something communally, thereby making ‘listening’ the most important parameter. In actual fact this aspect may be the most ‘liberating’ one for the musicians, the request to actually use their ears – the very thing which probably made them musicians in the first place.

Waves 3 by Peter Adriaansz

Waves 3 by Peter Adriaansz

However, I am a composer to the very nth degree of my soul, meaning that I construct certain edifices which are meant to stand and to be strong and which are very systematic in their approach. This area I control to the very smallest detail. This tends to go quite far because the ‘sound’ is itself also the form, demanding all kind of speculation and research into the nature, speed and motion of sound waves for example. All in all though, after many years of experimenting I feel I’ve found a balance which works – the balance between the giving and taking of freedom, between ‘on the spot’ choice and the tension supplied by the governing form. ‘Control’ in this aspect is something I just consider as my responsibility in order to really get to the bottom of things.