Oscar Bettison’s Presence of Absence

The liner notes for the album Presence of Absence – Oscar Bettison include a note by Aaron Hostetter on The Ruin, the Anglo-Saxon poem that forms the centrepiece of the entire work, and a Q&A between composer Oscar Bettison and Ensemble Klang’s Pete Harden. All further info, texts, credits and sales, can be found here: EnsembleKlangRecords.com

Notes on The Ruin

by Aaron Hostetter

Codicology is not destiny — but there are occasionally strange coincidences. One is the famous Old English lyric “The Ruin” (late 10th-century), whose brooding lines upon broken architecture & departed cities has itself fallen into ruin, heavily damaged towards the end, words now unintelligible. What remains is elegant & haunting, but perhaps hollowed out. It no longer contains the homiletic lesson most would assume was once there. Deprived of its joys, perhaps — though what is left appeals to more modern tastes for direct environmental observation and grim symbolism.

It is a critical commonplace to identify these ruins, with their hot springs, as what remains of the Roman city of Aquæ Sulis, now Bath in Somerset, which were wondered upon by the early Germanic settlers, who were dumbfounded by its stonework. This presumed mystification was then used to explain the frequent Old English phrase “enta geweorc” [the old work of giants, appearing five or six times in the extant corpus]. Much of our history of early England has been updated since these first readings. We know that the English did make some buildings from stone. We know they had more continuity with the Romanized Britons already in Albion. We know that the genre of speculating upon ruins was well-established in medieval Latin poetry (usually with a message made quite clear). And I would suggest that this poem does not have to be all that much older than its appearance in the Exeter Book.

What remains as less certain is generative & appealing: a crossing of images & words, sounds & structures. Allusive & eluding. Haunted & haunting. I’ve always felt that energy & tension in Oscar Bettison’s compositions, & it couldn’t make me happier to see this bejewelled enigma set by him.

Aaron Hostetter is Associate Professor of Old and Middle English at Rutgers University-Camden

Exeter Cathedral Library MS 3501, f. 124r, all rights reserved Dean & Chapter Exeter Cathedral

Exeter Cathedral Library MS 3501, f. 124r, all rights reserved Dean & Chapter Exeter Cathedral

A Presence of Absence Conversation

between composer Oscar Bettison & Ensemble Klang’s Pete Harden

Pete Harden (PH). When did you start developing the idea for Presence of Absence?

Oscar Bettison (OB). I started thinking about this piece in, maybe 2014. I think we agreed that I’d write a piece for my 40th birthday year in 2015, but in the end we decided that the premiere would be in 2016. I suggested a piece for voices, strings and Klang. I think you call that Ensemble Klang XL, right?

PH. Yeah, we started opening up the form of the group at some point. Having played for the first ten years almost exclusively as a sextet (2 saxes, trombone, percussion, piano, guitar), for which you wrote O Death back in 2006, we realized that an occasional project with extra players opened up all sorts of possibilities. So about once a year we do a project with an expanded line-up, sometimes existing works that fit into our aesthetic (Heiner Goebbels’ Walden, Michael Gordon’s Trance, Fausto Romitelli’s Professor Bad Trip, Olga Neuwirth’s Die Stadt ohne Juden) and occasionally new works, like Presence of Absence.

OB. Right. So, the plan was to write a piece for Ensemble Klang and strings with voices. And the idea for the texts and the concept of the piece came later.

Presence of Absence | Ensemble Klang XL with screening of Nikolaus Geyrhalter's Homo Sapiens

Presence of Absence | Ensemble Klang XL with screening of Nikolaus Geyrhalter's Homo Sapiens

PH. At an early stage in talking about the piece it was conceived as a large music theatre performance. We’ve performed it with the documentary film Homo Sapiens by Nikolaus Geyrhalter, and also in concert performance. How did these different versions develop in your mind, and is it still modular?

OB. I think the piece is set now in its form. I mean, I’m happy with the way it works with the film, if there’s any interest in presenting them together again I might make a version for that, but at the moment it’s concrete. As far as the dramatic piece is concerned, that didn’t really work for this, but some elements made their way into the opera I’ve just written (for which I also wrote the text) The Light of Lesser Days (2021). Also, this was the first piece I’d written for voice and ensemble since I was a student, so it this was an important piece for me in thinking about voice and ensemble. It’s also the first piece in which I wrote my own text. Both of these things have become quite important to me, so I think this piece is somewhat of a breakthrough for me.

PH. Michaela Riener, the mezzo soprano here, was asking how you see compositionally, and also sound- wise, the difference between an instrument and the human voice?

OB. Well, for me I think I love to hear a beautiful voice (like Michaela’s) just sing. I think there’s much more inherent poetry, much more emotional weight in a voice singing something simple, than an instrument playing the same thing. I feel I have to dig deeper to get the same thing in an instrument, and maybe that performer has to dig pretty deep too, but I like the voice to sing.

PH. Tell us about The Ruin, and when you first encountered this unique text.

OB. I think I first discovered The Ruin when I was 14. Since then I knew it was something I wanted to work with, so it was always on the backburner. When I started thinking about Presence of Absence I was immediately struck by the sober tone with which the poem described the crumbling buildings of the Roman Empire and the fact that the text itself, as a result of a fire several centuries ago, is also fragmentary – in other words: a ruin.

PH. And what was the process of working with this forgotten language, Anglo-Saxon? How do you go about setting it?

OB. Well, it was very tricky! I decided early on that I had to set it in the original language, I mean, a poem about looking back on a long past civilisation has to be in a language that has long gone extinct. But, like I say setting it was difficult. It has all the dark vowel sounds of English, with multisyllabic words like the Romance languages. But, I was determined to do it. I have to say how amazing Michaela Riener was at learning it. Within a couple of weeks of getting the score she knew the languages better than I did.

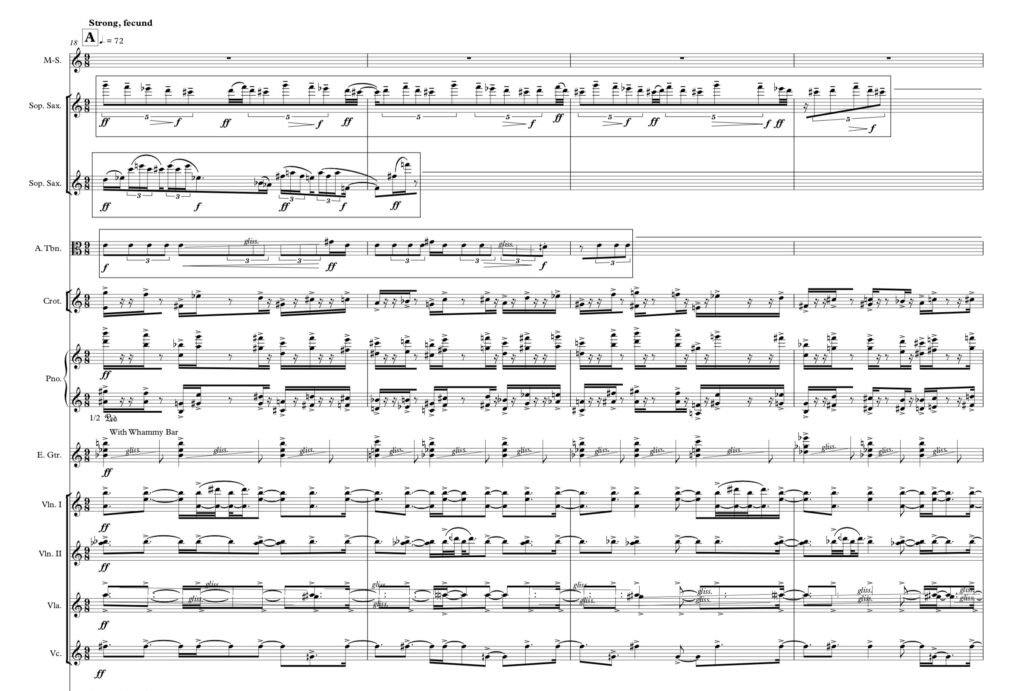

PH. One of things I love about your scores are the instructions for the musicians regarding atmosphere or emotion that come at certain sections. In Presence, we have things like ‘Strong, fecund’ (Mvmt 1), ‘Frozen, dreamlike’ (Mvmt 2), ’Sombre, opaque’ (Mvmt 3) etc. In your compositional process, do these instructions come after you’ve written the material, with the goal of nudging the musicians in the right direction, or do they come early in the compositional process, acting almost like placeholders for the material until it arrives?

OB. That’s a very good question. I actually sketch things out very quickly when I’m first thinking about a piece,

like a brain download, just putting everything down. One thing that I do with every piece is that there are words that just describe things that I’m thinking of, as well as specific musical ideas. Sometimes, those words do make it into the instructions, you’re right. I think ‘Strong, fecund’ was one of them.

Score excerpt from Movement 1 of Presence of Absence, Oscar Bettison

Score excerpt from Movement 1 of Presence of Absence, Oscar Bettison

PH. How does this work relate to O Death, your earlier large-scale work for Ensemble Klang?

OB. At first it didn’t relate to O Death at all. I mean, I was deliberate about that. But, you look at your work differently after it’s been performed, and I started to realise that in deliberately writing the opposite of O Death, the works are in fact related. Now, I think that they are two sides of the same coin. But that doesn’t mean that they’re a diptych. I think they’re part of a cycle:

Part 1. O Death (2005-7)

Part 2. Presence of Absence (2016)

Part 3. ? (2026?)

Actually, I know what I’d like to do for part three, and maybe we won’t need to get all the way to 2026 for that. Let’s see. What I do know is that I’d love to write another piece for Ensemble Klang.

PH. We shouldn’t ignore the circumstances surrounding the recording of this album. It was recorded in October 2020, during corona lockdown. For that reason, we were able to make use of the amazing De Doelen Concert Hall. But Michaela came down with a cold the day before the first rehearsal, so we ended up rehearsing without her and then splitting the recording across two sessions, separated by a month. On that first rehearsal day we could easily have said ‘this isn’t going to work, let’s postpone till we know we can do this’. But we pushed on, and in the end the album stands as a small symbol for the perseverance that we’ve all needed during these difficult last couple of years, and the beauty of what’s still possible when we work collectively.

OB. Why does everyone write Ensemble Klang such big pieces?

PH. Haha, well, I think it comes from both sides… we encourage it, we seek out composers with big ideas, but also because our concert and performance practice doesn’t occupy any traditional formats: we’re not looking for a 10 minute opener before playing a concerto; or we’re not looking for a complete repertoire of 7 minutes pieces. But in essence it comes down to a love for those larger musical statements, and the daring that it takes from the composer to take on those forms. There’s a passage in Roberto Bolano’s epic book 2666, where the character Amalfitano has a fleeting encounter with a pharmacist who’s only interested in short books and stories. The passage acts as a sort of apologia for Bolano’s book itself, and maybe helps put into words our own fascination with those larger works:

“He chose The Metamorphosis over The Trial, he chose Bartleby over Moby Dick, he chose A Simple Heart over Bouvard and Pecouchet, and A Christmas Carol over A Tale of Two Cities or The Pickwick Papers. What a sad paradox, thought Amalfitano. Now even bookish pharmacists are afraid to take on the great, imperfect, torrential works, books that blaze a path into the unknown. They choose the perfect exercises of the great masters. Or what amounts to the same thing: they want to watch the great masters spar, but they have no interest in real combat, when the great masters struggle against that something, that something that terrifies us all, that something that cows us and spurs us on, amid blood and mortal wounds and stench.”

Well, we have less blood, maybe some stench, but that moment where a maker is striving for something just out of reach, something unknown and new, certainly throws up an excitement for us, in our daily work, and a tension in the musical works and our performances of them. I think we’ve felt that excitement and tension in bringing Presence of Absence to life, and I hope that that also communicates here in its now recorded form.